Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

For many, the story of school desegregation in the United States starts with the Supreme Court ruling in the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954. While Oliver and Linda Brown, Ruby Bridges, and the Little Rock Nine deserve every accolade for their courage, the struggle to desegregate higher education was just as difficult and at least as significant.

It also began before the Brown decision in 1954. The legal strategies that proved successful in the 1950s for schools had been crafted and refined at the university level in the first half of the 20th century. They began to pay off in a series of court rulings that opened up all-white state universities to Black students. As these three images remind us, Black women were at the center of the struggle to integrate higher education.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Autherine Lucy applied and was accepted to attend the University of Alabama in 1952. However, university administrators rescinded her acceptance after learning she wasn’t white. Three years and a lawsuit filed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People were necessary for her finally to secure her spot.

Lucy attended two days of classes in February of 1956 before white mobs rioted on the campus for three days, at which point university officials suspended her, allegedly for her own safety. Lawyer Arthur Shore, pictured with Lucy, oversaw her second case against the University of Alabama. The microphones on the table highlight the national media attention to the case, which drew the ire of university officials.

Autherine Lucy’s courage made her a target of white supremacists and she temporarily relocated to New York City. Lucy married Hugh Foster in the spring of 1956 and toured the country with the NAACP. By the end of the year the pair returned to the South full time. Lucy remained committed to education. Like many educated Black women, Lucy became a career teacher whose legacy lived on through her students.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Charlayne Hunter’s (now Hunter-Gault) admittance to the University of Georgia (UGA) offers proof that previous pressure cracked the system of Jim Crow that structured the South. When Hunter enrolled alongside Hamilton Holmes in 1961, the pair became UGA’s first African American students. This photograph captured Hunter as she left the registrar’s office after officially enrolling.

The small crowd seen here pales in comparison to the angry mob that surrounded her dorm two days later. While racists were able to express their dissatisfaction with her presence freely and violently, Hunter had to remain stoic and composed. Though UGA officials followed Alabama administrators’ model by suspending Hunter and Holmes, a court order allowed them to return to campus and resume classes. She graduated in 1963 with a journalism degree and embarked on an illustrious career. Hunter’s persistence and success inspired and encouraged those who came next.

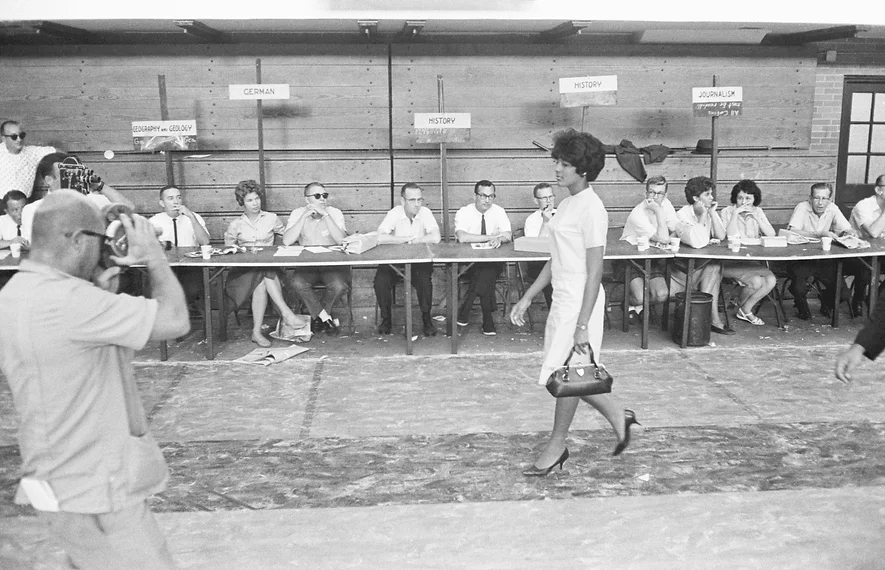

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Vivian Malone may have been one of those people Hunter encouraged. Years later, Malone named Autherine Lucy’s persistence as a source of inspiration as she and James Hood faced down Governor George Wallace to enroll at the University of Alabama in 1963. She graduated in 1965 with a degree in business management.

Even though Malone completed the mission Lucy started, her success at Alabama carried its own cost. The range of cold indifference to close stares displayed by the university’s registrar’s staff captures her experiences on campus. Simultaneously ignored and placed under a microscope, Malone had to remain poised and was acutely aware of what her presence represented. Malone’s attire, like that of Lucy’s and Hunter’s, communicated her preparedness and decorum, two qualities that were necessary to counter prevailing stereotypes about Black women and claim their dignity and autonomy.

This history illuminates the long struggle for educational equity in the United States. Greater attention to these three stories prompted long overdue formal acknowledgment. Alabama awarded Malone an honorary doctorate in 2000 to commemorate her career dedicated to advancing civil rights. The university recognized Autherine Lucy’s contributions with an honorary doctorate in 2019. UGA announced an annual lecture in Hunter’s name in 2021. Each woman’s journey highlights the incredible and lasting difference one individual can make.

Learn More:

“An Indomitable Spirit: Autherine Lucy,” in Our American Story, by the National Museum of African American History at the Smithsonian Institute, https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/indomitable-spirit-autherine-lucy. Accessed March 23, 2021.

Ford, Tanisha. Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

Richmond, Krista. “Holmes and Hunter-Gault: They Followed their dreams,” UGA Today, February 1, 2019. https://news.uga.edu/holmes-hunter-gault-georgia-groundbreakers/.

“Key Events in Black Higher Education,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, https://www.jbhe.com/chronology. Accessed March 20, 2021.

“Through the Doors: Vivian Malone,” University of Alabama, http://throughthedoors.ua.edu/vivian-malone.html. Accessed March 8, 2021.